Beyond the Pale, with Ghosts and GLLMs

A 4th-generation Litvak American traces her roots with the help of strangers and AI.

Lithuanian Proverb: Just as one calls into the forest, so it echoes back.

Twice last week, I dreamed about ghosts: invisible, disruptive spirits that shook beds and overturned tables. I woke up so spooked that I had to turn on the bedside lamp.

It’s no coincidence, I think, that the dream-ghosts arrived while I was trying to bring the dead back to life. I’d been hunting for clues to my great-grandparents’ lives in late-19th-century, Russian-occupied Lithuania, the spot from which they hauled themselves and their baby daughter by steerage to the New World. After decades of “wouldn’t it be cool if we knew…”, I dove into my maternal family tree with new urgency and the help of online genealogy tools: publicly searchable databases and distant relatives’ family trees on Ancestry, FamilySearch, and JewishGen.

My mother’s stories had brought her grandparents to life in the ways that mattered to her: they were funny, warm, simple people whose love story had started across the ocean. Their courtship began at a wedding when Hyman walked up to his older first cousin, Lena, and asked her to dance.

At first she demurred, “You should ask one of the girls your age.” (And, er, one not so closely related?)

"No," he insisted, "I want to dance with you.”

They would have ten children, not counting the ones who didn’t survive infancy. Great-Grandpa Hyman, a tailor and merchant, would die young of heart disease. Great-Grandma Lena, diabetic with one amputated leg, would rock contentedly in her rocker until age 98. Not that her life was easy: along with the labor of raising ten children, Lena endured the grief of surviving her beloved son Billy, my mother’s father, whose heart trouble manifested even earlier in life than Hyman’s. Yet my mother mainly remembered her grandmother smiling, laughing, and rocking.

These stories tell me where I come from, but not where I come from. Here in 2025, I need to place Hyman and Lena on solid earth within shifting borders. Lithuania and Poland were once one commonwealth, and the city of Vilna, or Vilnius, at times was part of Poland. Lithuania suffered the misfortune of occupation by Russia twice, the second time under Stalin. In Hyman and Lena’s time, Jewish people were corraled into one area called the Pale of Settlement, and Russian soldiers dragged away Lithuanian boys as young as 10 to fight in the czar’s army.

In the beginning, it was easy enough to mine gems from U.S. records: there were Lena and Hyman’s birthdates (1866 or 1864 and 1871, respectively), dates of arrival in the U.S. (Hyman in 1892 and Lena with baby Sara in 1894), and images of their headstones. There was a photo of my Uncle Dickie as a boy, too, looking very much like the bully who’d buried my mom in a pile of leaves and then gotten a hefty kid to ride over her on his bike—but no, I needed to stay focused on deeper strata.

I’m fairly sure that Hyman and Lena were born in or near Vilna within the Pale, but corroboration is scant and elusive. U.S. census records list their birthplace as Russia, as it officially would have been. Czar Nicholas I worked mercilessly to erase Lithuanian culture and identity, forbidding the use of the name “Lithuanian” for the Russian-controlled provinces, but I know how my great-grandparents identified themselves: as Litvaks, Lithuanian Jews. They would have stubbornly carried on speaking both Lithuanian and Yiddish at home, and nothing short of death could have made them relinquish their culture. The czar’s borders and edicts couldn’t cut through their being.

How do I know? Here’s another story:

When my mother was a child in Annapolis, a Jewish family friend saw her on the street and teased, “There’s that little Litvak!” To the kindly man’s dismay, she promptly burst into tears, thinking he’d called her a bad word. He patted her on the shoulder and explained that it was not bad at all; it was just her heritage.

But family stories carry different layers of truth than historical records—which also, to complicate matters, may distort and mislead.

When I hit impenetrable rock in database searches, I enlisted Lumo AI to suggest next steps. Yes, it may hallucinate three bs in blueberry, but a generative large language model (GLLM) like ChatGPT or Lumo can be remarkably helpful for this kind of project. And frankly, on terra incognita, I appreciate the can-do tone encoded within the algorithm.

Absolutely—let’s turn those solid breadcrumbs into a clearer picture of Hyman (Chaim Avraham) Reichel, Lena Reichel, and their daughter Sara. Below is a structured roadmap that mixes concrete record‑search tactics with broader context to help you move forward efficiently. —Lumo

Yes, let’s! Lumo pointed me toward their Maryland death certificates, which I was able to order online for a small fee. It was well worth the expense.

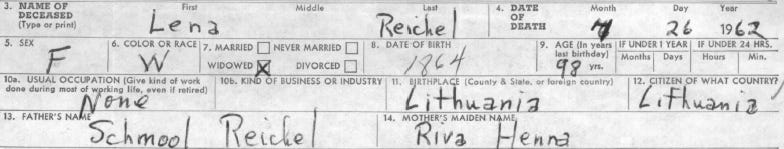

Lena’s 1962 death certificate listed her birthplace as Lithuania, which had become an independent country again in 1918. Her parents were listed as Schmul and Riva Henna Reichel. (Yep, her maiden name was also Reichel. Our family tree is a circle.)

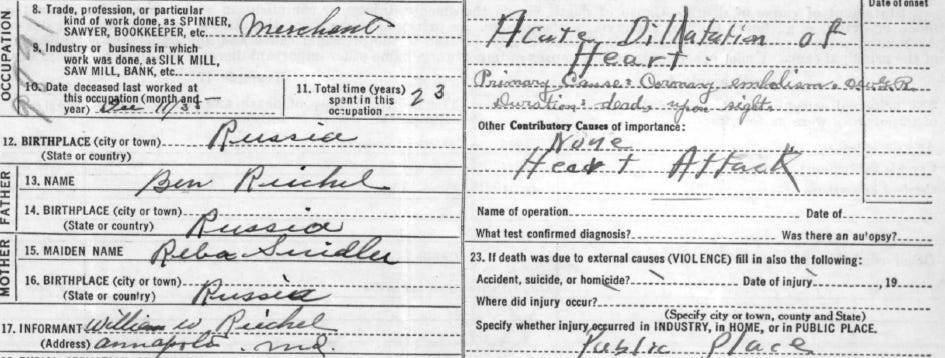

Having died almost thirty years earlier when the Republic of Lithuania was still fairly new, Hyman was still identified as Russian. His parents were listed as Ben Reichel and Reba…Seidler? I also saw that a heart attack took him in a public place. I drifted away to wonder whether someone tried to revive him or held his hand as he died…to imagine Lena in her rocker when someone came to tell her…but no, I needed to focus on knowable truths.

“Ben” Reichel, by the way, was an Americanization, a nickname, or just plain wrong. In this case I trust what is carved in stone. The day before, several helpful people in a Jewish genealogy group had translated Hyman’s tombstone thus:

Our precious father

Chaim Avraham son of Yaakov

who was the warden and member of

the Knesset Yisrael Holy Congregation

surrendered life to other living creatures

during the night of the 5th day of the Jewish week, 16th Kislev 5696

may his soul be bound in the bond of life

Maybe Hyman’s father was Yaakov and Ben, both. None of us is just one thing; like relational database tables, we have one-to-many relationships with the world around us and even with ourselves. There’s what’s bequeathed to us—the gifts and curses of the family, culture, and borders in which we land. Then there’s what we choose to do with it all: where we sail with pockets full of bread and coins and a head full of hopes and dreams; whom we love daringly without a thought for descendants’ cholesterol levels; what land we claim as our own, for ourselves and the next generations. We are all the words we say and all the things we do with our days until we surrender life to the living.

My hope is that the deeper I dig, the less ghostly my forebears will become.

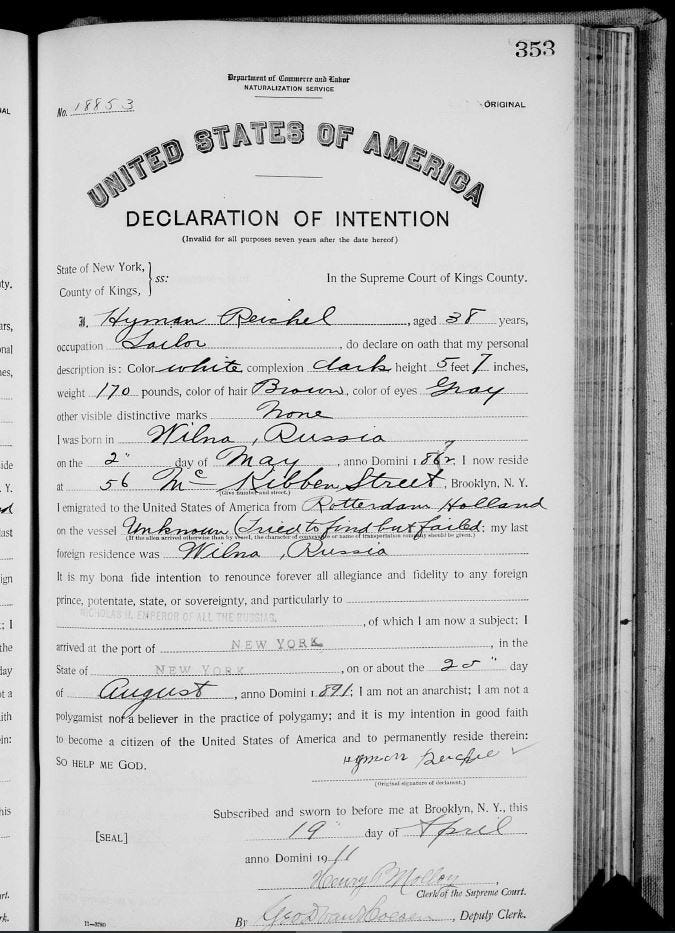

Here is my most treasured find so far: the document in which Great-Grandpa Hyman declared his intention to be a United States citizen and renounced “forever all allegiance and fidelity” to Russian Emperor Nicholas II.

I love this, Jody. A few years ago, my sister became interested in our family history and it kind of sucked me in too. There's something about understanding where we came from, how everything and nothing can change over decades and centuries, that we are here because of others' stories, that is captivating. That we arrive in this world when and where we do sometimes seems like a dance between chance and fate.

I just read your post and had to look up the Pale of Settlement and saw that it was where Jewish people were "permitted to live" in what was formerly Lithuania and technically at that time, Russia. It always surprises me when I see words like that because I simply do not and will not ever understand how a government (or in that case, kingdom) can decide who can live where based on religion and/or ethnic identity. WTF?? I realize that this is still happening around the world and I was privileged to grow up in the U.S. where such things were outlawed (although they seem to be galloping back to my dismay and disgust). I love that your grandparents were able to get to the U.S. and that you've been able to find out more about them. Thank you for sharing their story in your always beautiful way!