Light in Darkness

On the blind French Resistance leader Jacques Lusseyran and the inner light that guided him.

I was aware of a radiance emanating from a place I knew nothing about, a place which might as well have been outside me as within. But radiance was there, or, to put it more precisely, light. —Jacques Lusseyran

Sometimes, I feel trapped in a game of Trivial Pursuit. Card after card flashes before my eyes—the historic, the silly, and the suspect; the true, the false, and the willfully slanted—all blurring together in a fast-shuffled virtual deck, each fact half-forgotten as soon as it flashes past.

Other times, especially when a search reaches back into the resonant past, the words on my screen change me and my relationship to the world. Like a beam of light in a dark room, they remind me of something real and true.

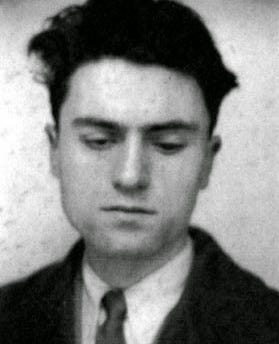

Months ago, a friend recommended Jacques Lusseyran’s 1963 And There Was Light, the WWII memoir that inspired the novel All the Light We Cannot See. Last month I finally set out to read Lusseyran’s book, but by then I’d forgotten the title and even the author’s name. French Resistance—blind—light. A search for “blind French Resistance leader” quickly pointed the way. I bought the ebook and then spent my evenings lost in it. It’s such a luminous story, so deeply personal and profoundly spiritual, that my own words can’t touch it.

So I’ll start with a non-trivial question:

The Nazi regime almost succeeded in devouring Europe through a combination of brute force, mechanistic efficiency, and unrelenting propaganda. Long before the U.S. and Russia joined Allied forces, who resisted the Nazis, how, and why?

One true answer is:

A blind teen and hundreds of other young Parisians formed a hidden information network in occupied France. Each did it for their own reasons: patriotism, religious belief, a love of freedom and justice, and a hatred of tyranny. For Jacques Lusseyran, the “how and why” encompassed all of those things but also went deeper. He lived by an inner light, one that even a concentration camp couldn’t extinguish.

The Corner of the Desk

At the beginning of his memoir, Lusseyran describes a joyful early childhood with smart, cultured, loving parents.

My parents were protection, confidence, warmth....I passed between dangers and fears as light passes through a mirror. That was the joy of my childhood, the magic armor which, once put on, protects for a lifetime. —Jacques Lusseyran

Then when he was almost eight, a schoolmate jostled him hard enough to send him tumbling. When he fell, his right eye hit the corner of the teacher’s desk. The impact drove his eyeglasses so hard into his face that they gouged out his right eye and rendered his left one permanently blind. In a moment he went from the “clear water” of an idyllic childhood into a world of outer darkness.

Sometimes, children are born sensing the world in ways different from the ordinary. Other times, they get scarlet fever or get their eyes poked out. Whether by nature or accident, each finds a way forward with or without loving parents, dedicated teachers, and assistive technology. Lusseyran had all three: his mother learned Braille with him, and his parents fought successfully to keep him in a regular classroom, where he took notes on a Braille typewriter. Once he’d adapted to this way of learning, he became an academic star, especially in the study of languages and literature.

When I was fourteen I was a small edition of the Tower of Babel.

Lusseyran’s particular area of interest and study was German language and culture, a store of knowledge that would help him later. When he was a prisoner of war at Buchenwald, his fluency in German and other languages would save his life.

The Lighted Path to Resistance

Lusseyran’s school years weren’t all study; there were friendships, family holidays, music, and a deep connection to the natural world. On long walks he explored the countryside differently than he had as a sighted child. As he explained it, vision distances us from the object of our gaze. A tree becomes a thing out there that we look at and then describe. But when you touch and feel a leaf to know it, then you enter into relationship with it.

The gifts of Lusseyran’s blindness would help keep him and hundreds of other Resistance operatives safe during the brutal Nazi occupation of France and the Vichy government’s complicity.

Outer darkness. Here it was. A place worse than any melodrama, where men must shout at the top of their voices to be heard, where they talk honor when they want to dishonor, and fatherland when they want to pillage.

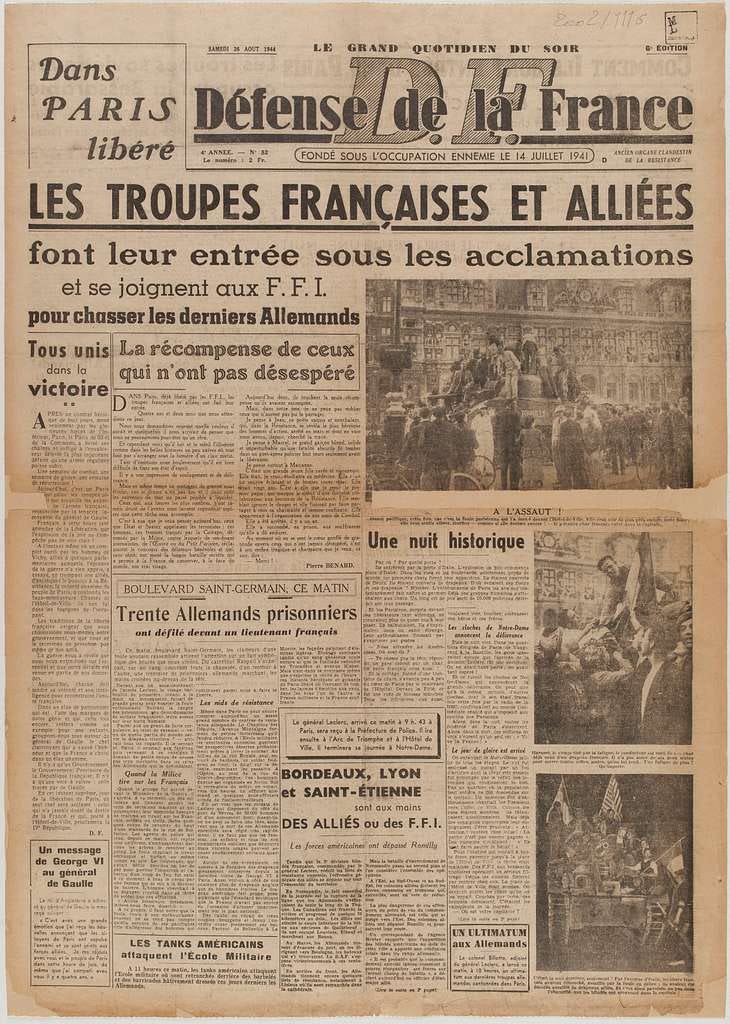

Ten years after he fell against the desk, he would found and lead a group called the Volunteers of Liberty. They were teenage schoolboys; they carried no weapons; instead, their self-appointed mission was to gather and spread the truth. Hiding in plain sight as “harmless youngsters,” they published and distributed a clandestine newspaper, smuggling real news through the firehose of Nazi propaganda. Eventually, they would merge with a larger Resistance group called Défense de la France.

With his heightened attention to details and keen sensitivity to voices, Lusseyran was a nearly infallible judge of character. Thus the group voted to put him in charge of recruiting. When a young person expressed interest in the Resistance, they would be told, “Go talk to the blind man.” Over the years, almost 600 recruits would make their way by appointment to Lusseyran’s private room in his parents’ home.

From Lusseyran’s perspective, it was not so much knowledge or courage that guided him but the grace of an inner light.

The light which shone in my head was so bright and so strong that it was like joy distilled. Somehow I became invulnerable.

All his skills and talents aided his Resistance work, but the most important was the one he couldn’t explain, the one he shared with only his closest friends. It seemed that lies didn’t have a chance in that light.

Buchenwald and Beyond

Eventually, Lusseyran interviewed a recruit whose past exploits and posture of earnestness were so compelling that he couldn’t be sure. Instead of the usual clarity, he saw something like a “black bar” between the man and himself. He expressed his misgivings to the leader of Défense de la France, who decided they couldn’t afford to turn away a recruit with such desperately needed skills. That recruit, Elio, would betray them all to the Gestapo in July of 1943.

After six months in prison, Lusseyran was transported to Buchenwald. There, the SS kept him alive for his multilingual translation skills. Some friends from Défense de la France were with him for a while, but then they were transferred to hard labor, and he was a blind man alone. Yet Lusseyran became one of the 30 out of 2,000 French prisoners who survived Buchenwald. Through his ability to comfort and inspire others, he won the affection and protection of other prisoners, particularly the Russians. Even in a concentration camp, he lived for and by something beyond himself. Bathed in that inner light, he also lived without fear.

American soldiers liberated Buchenwald in April of 1945.

Despite his heroism and stellar academic record, Lusseyran had to fight to become a teacher in post-war Paris. During the war, a Vichy decree barring “invalids” from public employment had canceled his acceptance to the École Normale Supérieure, an elite university for future French academics. Incredibly, even after the war, the government wouldn’t let him in. Eventually he moved to the U.S., where his first job was as a lecturer in French literature at Hollins, my alma mater.

Lusseyran and his wife Marie died in a car accident in France in 1971. They were near Juvardeil, a village where he’d spent happy holidays as a boy.

There will always be a chasm between trivia and truth. The truth may be hard to express and harder to believe. I’m thankful that a man who lived fully in both the head and the heart took the time to tell his story.

Hollins? I thinking that is from where my daughter-in-law graduated.

I may check out the book. I’m attracted to the light in people….

Carol Richardson

What a beautiful reading of a memoir of courage and resistance. You are really excavating amazing connections with your own paths too! I also loved your excepts about vision, which really resonate for me, especially now😿