Empathy: every violent news story seems to announce a dearth of it. But is lack of empathy really the problem, or is something more complicated going on? What is the difference between empathy and sympathy, and which is better for healing the world? Mulling over these questions, I thought of the Austrian-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke.

Rilke liked to look inside of dogs. Happily, this practice did not involve opening up the dogs or otherwise inconveniencing them. Instead, Rilke imagined he could “in-see” a passing dog with a kind of exploratory, radical empathy, à la Quantum Leap:

I love in-seeing. Can you imagine with me how glorious it is to in-see a dog, for example, as you pass…to let yourself precisely into the dog’s center, the point from which it begins to be a dog, the place where God, as it were, would have sat down for a moment when the dog was finished, in order to watch it during its first embarrassments and inspirations and to nod that it was good, that nothing was lacking, that it couldn’t have been better made….Though you may laugh, if I tell you where my very greatest feeling, my world-feeling, my earthly bliss was, I must confess to you: it was, again and again, here and there, in such in-seeing — in the indescribably swift, deep, timeless moments of this godlike in-seeing.

—Rainer Maria Rilke in a letter to Magda von Hattingberg, Peb. 17, 1914, transl. by Stephen Mitchell

I read that passage many years ago and then set about trying to “in-see” my cat, who happened to be sashaying past the couch. I could observe her closely—that variegated, soft fur fringed with sunlight; those toe pads lifted skyward for a brisk, businesslike bathing. Close attention rewarded me with a surprise or two: for example, I’d never noticed that dark spot on her pink nose before. With my head near floor level, from a discreet distance, I could watch her scoop up water with a rough, curled tongue, and I could imagine what it might feel like to drink that way. (I think it would be fun.) I could bury my nose in her fur and inhale her clean kitty smell.

But nope, I could not barge into my cat’s consciousness and set myself down in there. Not only was it impossible; it felt rude to even try. That inner space of being was hers, not mine. I was just lucky that this graceful, mysterious, nice-smelling creature deigned to share my digs in exchange for petting and Fancy Feast.

So what was Rilke going on about? How and why did he presume to be a dog-indwelling god? There is a small clue in the immortal words of John Berryman from “Dream Song #3”:

Rilke was a jerk.

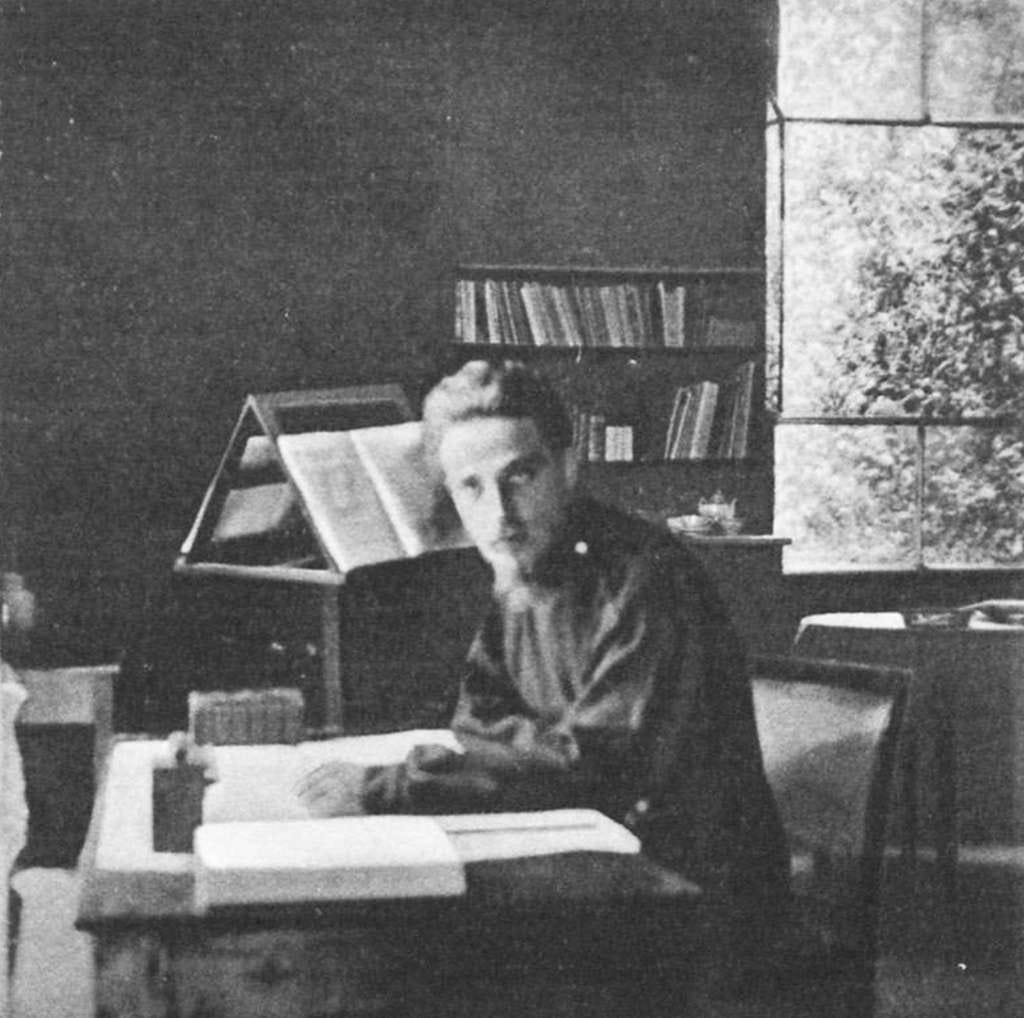

Rilke’s poems are achingly beautiful. There is nothing else like them. I’ve read Stephen Mitchell’s translations of the Duino Elegies so many times that I know stanzas by heart. I wept over the first elegy in a Denny’s booth about a quarter of a century ago, salting my pancakes with tears. Granted, I’m not sure if the original German would affect me as strongly. As Coleman Barks did with Rumi, Mitchell reimagined and refreshed Rilke’s poems in modern English free verse. It’s as if Mitchell tried to “in-see” the poems themselves to get at their essence. I still don’t know if the result was exactly Rilke. Anyway, translators’ liberties or no, the world acknowledges Rilke as one of the greatest poets of the 20th century. One of my heroes, the Dutch diarist and Holocaust victim Etty Hillesum, carried her battered copy of Rilke on the cattle car to Auschwitz.

But Rilke the man was a world-class jerk. As summed up in a Washington Post review of the biography Life of a Poet by Ralph Freedman:

Life of a Poet makes clear that this hollow-eyed communer with angels, Greek torsos and death was not merely a selfish snob; he was also an anti-Semite, a coward, a psychic vampire, a crybaby.

Ouch. But narcissists—people whose psyches never grew past babyhood—do often whine. Speaking of kids, Rilke apparently didn’t bother to “in-see” his abandoned daughter before plundering her education fund to traipse around Europe and have epiphanies in castles. Yet he was lavish with self-pity.

Narcissism is the key, I think, to claims of godlike oneness with unsuspecting dachshunds or anybody else. Rilke’s “in-seeing” was harmless, but it was a sign of his inability to accept where he ended and another creature began.

Now a century and an ocean away from the turrets where Rilke wrote his masterpieces, I’m thinking about a brilliant former friend who is dying without any idea why his daughter no longer speaks to him. The situation is as tragic as it is impossible to resolve in any other way.

Empathy comes from the Greek em- + pathos: “being put into a state of deep emotion.” This is pretty much what we want and expect writers and artists to do—to empathos us. We want them to make us feel another’s being so deeply that it is as if we are them. What a relief to escape from ourselves for a little while, to step into other lives and to come out feeling larger and wiser. But in real life, we can’t feel other people’s feelings for them. It’s creepy to even try. Empathy can even contribute to violence.

Sympathy, on the other hand, means “affinity with.” When first used in the 1570s, it was “almost a magical notion at first; used in reference to medicines that heal wounds when applied to a cloth stained with blood from the wound.” What an extraordinary metaphor for how we can help and heal each other at a respectful distance. Sympathy is an alchemy that takes place only in relationship with a fellow creature and their wound. Nobody presumes to crawl inside of anybody. We ask them where it hurts and, with their permission, apply the balm. In the case of animals, who can’t understand what’s going on, we may have to forego the permission.

One of my cats has a cancerous tumor on his third eyelid. (Cats have more eyelids than I would’ve thought possible.) His surgical consult is later this week. Meanwhile, I have to give him pills and put moisture in his eye twice a day. He’s made it clear how he feels about that: at medication time, sometimes I have to chase him up the attic stairs and scoop him out from under the bed. I tell him gently that I know it doesn’t feel good, that nobody likes to get goopy stuff in their eye, and I’m very sorry. The tone of my voice helps him know he’s safe, but otherwise, I’m just making myself feel better—i.e., like less of a jerk. What actually helps him is the liquid to replace his tears, not my outpouring of empathy.

I think every parent and pet caretaker knows what it’s like to have to be the “bad guy.” Our empathy for our fellow creatures may or may not be helpful for them or us; it may or may not inspire us to take the right action for their well being.

Some of us have found ourselves to be psychic flypaper for the broken souls called narcissists. Or maybe a better comparison is that they draw out our empathy like snake charmers. They make us feel special: they “get” us; they need us. Then they demand we pour out our life’s blood over their self-inflicted wounds. Finally snapping back to ourselves and severing the connection, we may feel both guilt and grief, though we are not responsible for their pain. What a strange and dangerous game on any level—personal, national, or global. The only way to win is not to play.

Profound <3

Thank you for this! It’s given me a lot of insights and Ah Ha! Moments. I used to teach drawing workshops and it always amazed me that when people are drawing you can almost see inside their souls. Their false personalities fall away and their true self is laid bare, although they themselves usually didn’t realize it. When they did realize it, they would exclaim that they’d found a self they’d forgotten. Or like a banker before the 2008 financial crash said with a shocked expression, “You can’t fake this, can you!” He didn’t come back to the class again. I don’t know if that’s a form of “in-see”, but it was quite surprising and very accurate. Even so, I’ve too often become “psychic flypaper” for narcissists. I wonder how we can teach children from an early age to protect themselves from these devils?