The Core of the Matter

Or, why I worry about skills-based English instruction.

It’s a gift to be able to help kids read literature and write about their own experiences. It is. So why do I feel so kvetchy on this crisp fall morning?

Although I’ve never taught in classrooms, I’ve been writing English lessons as a contractor for educational publishers for more than a quarter of a century. My sister, an ESL teacher, has bluntly questioned the wisdom of letting non-classroom-teachers write instruction. I can only respond that I get hired for two reasons: 1) I’m good at fleshing out other people’s outlines; 2) teachers can’t always (or don’t always want to) write clear, engaging lessons to a publisher’s specs. And like every other paid writing job, developing content for ed. pub. is all about writing to spec.

Yet I genuinely love reading and writing and want to share the power of language with kids. I remember what it was like to meet a transformative metaphor and then to try to craft my own—to smudge chocolate on the pages of The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze and scratch out poems and stories in the loopy cursive of a 13-year-old girl. In fact, if I could save memories from a fire, a few books and friendships are all I’d carry out of the flames from that difficult year. (The notebooks can burn; those stories and poems were just a wobbly start—or in language arts terms, “prewriting.”)

It’s a gift to be able to make a living with meaningful work. So surely I’d save a few lessons from the flames of more recent years, stuffing them into a knapsack and shlepping them out on my slightly stiff middle-aged back—right?

The problem is that I don’t feel as if I’m helping kids like reading and writing anymore. These days, English textbooks are all about abstract skills: students learn to analyze a poem the same way they’d dissect a pithed frog, seizing its theme with tweezers and holding it aloft like a still-beating heart. Each year, the lessons become more soul-suckingly skills-driven than the last; accordingly, each year I feel sorrier for the kids who have to slog through them.

I also feel sorry for myself and my fellow editorial freelancers as our flat-fee payments dwindle. Lessons are widgets, and they fetch what the market allows. Not only have our fees not kept up with inflation, but the hourly rate is actually lower than it was 15 years ago. You want fries with that lesson on analyzing recurring themes? OK, fries but no healthcare.

But never mind about the grownups and our hospital bills. Here’s a carefully constructed paragraph about healthy food choices! Look, the accompanying stock photo shows children of every hue beaming at their nutritious lunches. If they skip the fries, maybe they won’t need healthcare when they’re our age.

If you peer closely at my imaginary paragraph, you’ll see a notation in the margin that looks something like this:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.7: Integrate information presented in different media or formats (e.g., visually, quantitatively) as well as in words to develop a coherent understanding of a topic or issue.CCSS stands for Common Core State Standards. Since 2010, the Common Core has shaped English curricula for public schools in many states of the U.S. The stated aim is noble: “to prepare all students for success in college, career, and life by the time they graduate from high school.” But I’m afraid the tyranny of these dictates will be the death of the humanities. I’m afraid it will actively discourage the kind of thoughtful life that gives meaning and purpose to academic skills.

Skills-based standards are way older than CCSS, but I think the Common Core represents their triumph. Its trans-state adoption turns the study of English into a kind of bloodless bean counting: instead of learning how to love literature—how to grow into the questions that great writing poses—kids read to assimilate individual, disjointed skills to pass standardized tests. The literary selections are just vehicles.

About those standardized tests: a few companies make a fortune developing and administering them—the kind of money that sways policy and shapes curricula. Skills are testable; that feeling when a metaphor lifts your heart up out of your chest is not. Out you go, feeling of upliftment! At least partly in the name of profits, we’re teaching kids to assimilate dead bits of their dissected cultural heritage. It’s like Borg Lit 101.

These days, if a textbook asks students to get at the heart of a story, it’s only incidentally. The real goal is to check off the box, “determine a theme or central idea of a text.” Without alignment to the Common Core, English programs have little chance of state adoption. The tyranny trickles down to the classroom, too: if they don’t teach to the tests, teachers themselves may end up with failing grades. Yet great classroom teachers like my friend A. still try hard to provide rich context for abstract skills. Then along with “will a student’s sneeze give me COVID,” they have to worry about whether someone caught them straying from the objective.

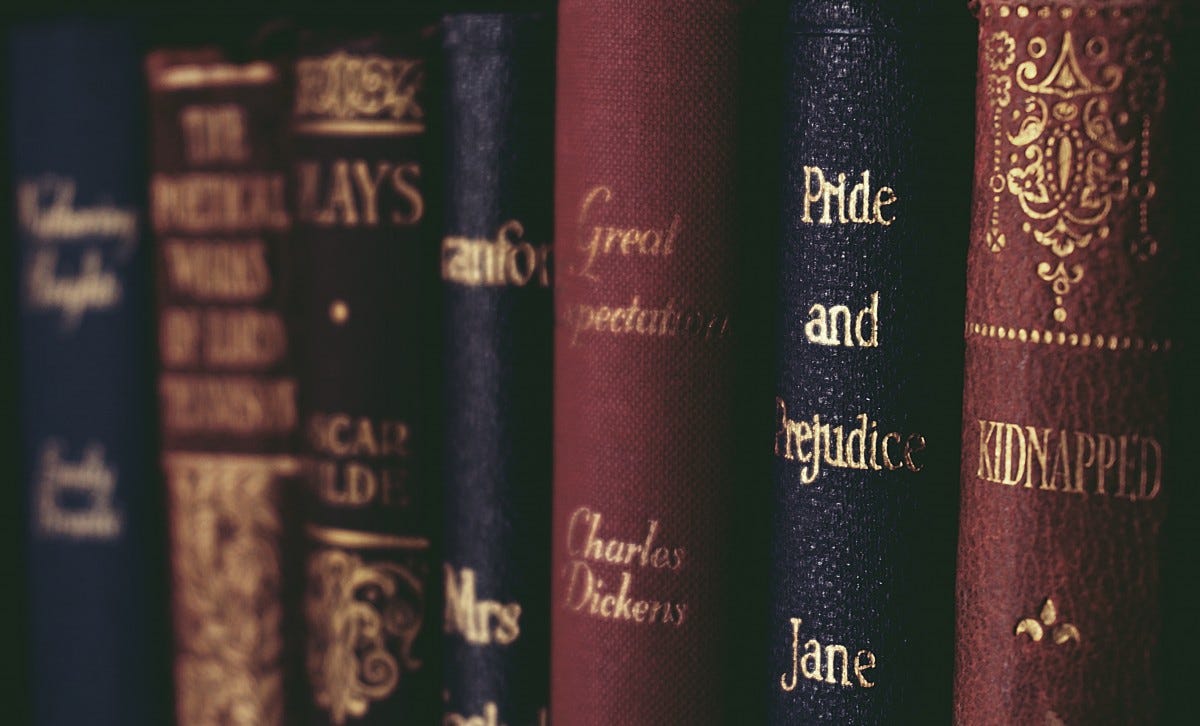

Somewhere on my bookshelf is a high-school English textbook from the last century that distinguishes between great and merely correct writing, between a soaring soul and a checked box. (I plucked it off a folding table at a hippie yard sale years ago.) It expresses an educational philosophy that I grieve the loss of: Look, we don’t pick apart great literature to sort it into boxes; we immerse ourselves in it to let it buoy us up. Or something like that.

Of course, the problem with that musty old book is that it’s full of dead white men with a token Emily Dickinson poem tucked meekly into a corner. Textbooks that embrace the diversity of human experience are cause for celebration. So are the voices of talented American poets like Alberto Ríos, Li-Young Lee, and Naomi Shihab Nye. Why not draw a connection between Homer’s Odyssey and Suzanne Vega’s song “Calypso,” as a 2005 literature textbook did? That “different media” lesson rocked—and at the same time, it taught kids that the whole story changes with a change in point of view.

But reprinting real literature and even song lyrics costs money, and the underbid publishers say they can’t afford to pay. There are still the old public domain works, but then we’re back to the scribblings of dead white guys, some of which are glaringly racist and misogynist. Wait, can’t we teach kids to place literature of the past in cultural context and glean its universal truths? I know T.S. Eliot was an anti-semitic prig, but I still recite passages from The Waste Land to myself in difficult times. Can’t we help kids wrestle with messy human inconsistency? But context gets tossed when teachers have to teach to the tests.

Accordingly, publishers teach the Common Core skills mostly with safe, cheap writing for hire. Some of it is very good, but as somebody once said about a poem in a college writing workshop, it’s not for the ages. Nothing is for the ages, anymore. Yeah, I know: what ages? We’ll probably all be drowned by climate change in another quarter century, anyway.

This week I’ve been drafting a lesson on writing a personal essay. The kids are supposed to write about an experience that changed them or taught them something new. The selections safely model the skills and also check the right boxes for diversity and inclusion. I’m actually proud of my work, and I know the talented editor will make it even better. I’m just worried that overall, we’re shaping a generation that won’t feel or think deeply about important matters. As a result, I’m afraid, they’ll never get at the living core of their own stories or place them in a shared context.

That’s just fine with the bean counters of the world, I know—but the smoke is in my eyes and I’m shifting from foot to foot. The children are huddled on the blacktop, waiting for instructions. The alarm is ringing in my ears, and I’m trying to think what I should run back into the fire to save.

Why can't we have it both ways? Teaching skills that check the boxes, AND lesson plans that develop a love of literature? Does it have to be a binary thing? Aren't teachers like A. doing just that? Maybe the exception rather than the rule? Anyway, great piece. I hope this was therapeutic for you! And bring a fire extinguisher with you if you have to rush back into the fire.