Two Kinds of Stories

A last road-trip installment and some thoughts on the stories behind our American situation.

Easter Sunday and the last day of Passover have arrived on the heels of the 250th anniversary of Paul Revere’s midnight ride: liberation from death, liberation from bondage in a foreign land, and liberation from despotic tyranny.

If the theme is liberty, another anniversary offers a warning against people who are dead set on achieving their ends by any means. Yesterday was the 30th anniversary of the deadliest act of domestic terrorism in American history. On April 19, 1995, former U.S. army soldier Timothy McVeigh and another homegrown extremist bombed the Oklahoma City federal building in the name of a particular story of American government. They killed 168 people, including 19 children.

I couldn’t help but think of that attack as I set down the last chapter of a cross-country road trip, starting this time from Oklahoma City.

A. and I were on our way to Memphis, where I’d splurge-booked a historic hotel for the night. We were going to spend most of the next day exploring the city and then drive to Nashville, from which A. would fly home the following day as I continued on to Virginia.

Driving along I-40 E, we listened to part of Jill Bolte Taylor’s book My Stroke of Insight: A Brain Scientist's Personal Journey, an account of her massive stroke at age 37 and its aftermath and implications. As she tells it, when the rational, calculating left hemisphere of her brain went offline, a feeling of blissful oneness with the universe arose alongside her physical pain as she lay near death. As she slowly recovered and her mother helped her relearn the ways of the world, things like money and politics seemed laugh-out-loud silly to her expansive, limping brain. People do what?

Fascinating though her story was, alas, we could take only so much of her voice. A folk playlist suited better for most of the seven-hour drive.

Then near Conway, Arkansas—about two hours from Memphis—the soothing voice of Google Maps announced:

There’s an object in the road ahead.

Um, thanks. How far ahead? Which lane?

Pretty close, it turned out, and ours. Afraid to swerve on a busy highway, I tried to straddle the blown truck tire, thereby discovering why Arkansans call those things “tire gators.” The thick coil of rubber chomped onto the underbelly of the car, and a terrible racket arose as dragging metal crumpled against asphalt at 70 miles per hour.

Back home a few days later, when the experience had become a story in my head, I thought of James Thurber’s 1933 comic masterpiece My Life and Hard Times. In it he describes the Thurber family car, an old crank-engine jalopy that had to be push-started, and the epic prank his brother played on their father.

But to get back to the automobile. One of my happiest memories of it was when, in its eighth year, my brother Roy got together a great many articles from the kitchen, placed them in a square of canvas, and swung this under the car with a string attached to it so that, at a twitch, the canvas would give way and the steel and tin things would clatter to the street. This was a little scheme of Roy's to frighten father, who had always expected the car might explode. It worked perfectly. That was twenty-five years ago, but it is one of the few things in my life I would like to live over again if I could. I don't suppose that I can, now. Roy twitched the string in the middle of a lovely afternoon, on Bryden Road near Eighteenth Street. Father had closed his eyes and, with his hat off, was enjoying a cool breeze. The clatter on the asphalt was tremendously effective: knives, forks, can-openers, pie pans, pot lids, biscuit-cutters, ladles, egg-beaters fell, beautifully together, in a lingering, clamant crash. "Stop the car!" shouted father. "I can't," Roy said. "The engine fell out." "God Almighty!" said father, who knew what that meant, or knew what it sounded as if it might mean.

It ended unhappily, of course, because we finally had to drive back and pick up the stuff and even father knew the difference between the works of an automobile and the equipment of a pantry.

In the depths of the Great Depression, a story that funny surely counted as a public service. Here in the middle of our own dark wood, it still does.

But back to the tire gator incident of 2025: while it was happening, it wasn’t at all funny. If somebody had said “the engine fell out,” I probably would’ve believed them. We pulled over to the side of the road and caught our breath, two discombobulated women stranded in Arkansas with tractor trailers whizzing past. Insisting I stay put, A. climbed out from the passenger side to take a look under the car. She suggested slowly backing up to see if it would dislodge the shadowy, dragging thing, which we still thought must be the tire itself. It was a good idea, but no luck: the racket only got worse.

Minutes later, when I was about to call AAA, a black car pulled over ahead of us and then backed up. We locked the doors and waited to see who got out.

A small man with a wispy gray beard limped toward us, his left knee sleeved in a brace. He looked harmless enough—at least, we could “take” him if need be—and somehow familiar. Then again, at this age, most faces look familiar.

We rolled down a window and explained the situation. He said, “I’m gonna get under there and take a look.”

“Thank you,” A. called out, “but please be careful!”

He peered in the window with a slightly defiant expression. “Sweetheart,” he said, “I’ve had 15 surgeries. A power line fell on me. My teeth were crushed. I’m not worried about this.”

Well then. I wished we could hear the story of the calamity and his recovery—how it had happened and how it changed him—but the breakdown lane of I-40 was not the place to ask.

He crawled under the car and then emerged with a diagnosis: “There’s a metal plate that got pulled loose. It’s hanging on by one bolt. I’m gonna zip-tie it up so you can get to the next exit.” He limped to his car, fished out a handful of small zip ties, and then came back to jury-rig the plate.

When he emerged from under the car ten minutes later and came back to the window, one of his fingers was bleeding. Appalled, we offered our first-aid kit.

“This?” He wiggled the bloody finger. “Honey, I cut this finger clean off before. This is nothin’.”

It occurred to me that the zip ties must’ve come in handy for many things in his perilous life—like, for example, reattaching severed digits.

We thanked him profusely, after which he insisted, “This is what we’re supposed to do. I couldn’t see people who needed help and just drive on by.”

I wanted to send him some money in thanks. I had the feeling he could use it, particularly in light of what’s happening to our social security system. He may have been fine, but there was something about his solemn demeanor and the way his traumas spilled out—along with defiant pride in surviving them—that made me guess he was alone with his knee brace and PTSD.

At first, he declined. “I didn’t do this for money,” he said gruffly. After I explained it would make me feel better, he nodded, “If you want to, all right.”

He asked A. to follow him to his car to get the payment info off his phone. “Don’t get too close to the car,” I whispered, on the alert again. But he just held out his phone for her to screenshot and then went on his way.

The jury rig didn’t last long, but we made it to a gas station in Conway, where I called my brother for advice and then AAA for a tow. Meanwhile, A. went into the little convenience store to use the restroom. When she emerged, she was accompanied by two men, one old and one young, who proceeded to jack up my car without so much as a by your leave. Stressed and irritable, I was about to say, “HOLD ON!” One really shouldn’t mess with a stranger’s car without asking. On the other hand, what could it hurt? I explained that we had a tow truck coming to take it to Walmart Auto.

The old guy harumphed, “You don’t wanna take it to Walmart. They don’t know how to do nothin’ but change the oil. They’ll act like they do, but they don’t.”

After a look under the car, he said, “That there’s your skid plate. That’s what happens with them tire gators—they can pull it right off. Same thing happened to my truck a year ago, and I still ain’t replaced it. You’ll be fine. We just need to take it offa there.”

They unscrewed the remaining bolt and dragged out what looked like a crumpled alien jaw vomiting up a dusty shroud.

I still felt doubtful. The convenience store clerk, who’d come out to watch, asked the old guy, “Should we call Jerry?”

They called Jerry, whoever he was, and then handed me the phone.

“Yep,” Jerry said, “that’s just the skid plate. You can keep on to where you’re going and get it replaced when you get home. Just don’t go off-road.”

When the tow truck driver arrived, the other men hailed him: ”How’s bid’ness?” He crawled under the car, too, and concurred with the others.

We thanked them all warmly.

“That’s how we do things here in Arkansas,” the old guy boomed heartily.

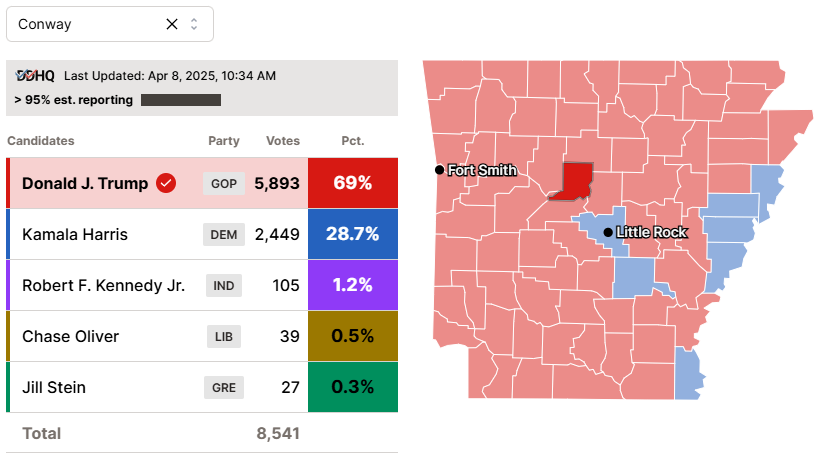

We were two respectable-looking white women in a nice car, but I’d like to think those Arkansan Good Samaritans would help anybody in need. I believe they would. Of course Conway, Arkansas, is deeply conservative; I wouldn’t expect anything else. At the risk of broadsiding you with what’s on my mind, I’m still trying to get my head around the fact that this little red boot and communities like it step to the tune of a venal man who helps no one, values nothing, and is currently presiding over the dismantling of our constitutional system and the economy. People did what?

I know it’s not their fault. In their decency, most rural Americans couldn’t guess how cynically and shamelessly they’d been lied to. In carefully shaped and filtered media clips, the wolf wore the face of everyone but himself. He was the huntsman saving Little Red Riding Hood from people with wolf masks photoshopped onto their faces; he was the victim, too, requiring good men to do violence on his behalf because, he said, the jury had been rigged.

God knows, these aren’t the only fake and distorted narratives that have wrapped around our amygdalae like tire gators. But in 2025, they are why we’re in the emergency lane. The bolt of everyday decency still holds, but our civic life has pulled loose from its anchors of charity, trust, and a shared American vision. I’m glad it’s making a godawful racket because that’s how we know something is wrong.

There are two kinds of national stories: ones that are rooted in literal and moral truth and subject to revision, correction, and growth; and ones that lie relentlessly in the service of grifters, authoritarians, and ideologues.

The individuals involved are declaring their power to define reality, independently not only of judicial but of all verification.

—Holocaust Historian Timothy Snyder, “The evil at your door”

How to tell them apart? When the powerful spinners of narratives begin to transport us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences, it will be crystal clear but too late. For non-citizens transported and imprisoned abroad without due process, it already is. Now, while there’s still time to remember who we are, I know no better touchstones than our founding documents with their wise checks and balances, the first-person stories of real people who are hurting, and this:

You too must befriend the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt… (Deut.10:19)

I love you, America. Happy Easter, Chag Sameach.

It's always good to hear that there are good Samaritans out there.

My dad was a big fan of James Thurber and that story made me think of him telling us about some of his favorite parts in Thurber books. 😊

I'm glad the 'tire gator' didn't scuttle your trip too badly, and that you and your companion are safe. A blessed Passover to you and your family and friends who celebrate. Hugs from the 505!

People did what?