I took notes on my phone during last month’s cross-country drive—when I wasn’t driving, that is. Mostly, I wrote down bits of dialogue from quirky strangers. Below is a quote from a convenience store clerk in southern Colorado in response to my brother’s request for a tire gauge:

If we got one, you don't want it. Go on over to NAPA. Don’t trust our air machine, either — use the one at Loaf n Jug.

She may have been just a disgruntled employee, but all along the way, people were honest, plain spoken, and helpful like that. A month later, I’m zooming out to think about the character and history of the places we passed through.

We drove through sparsely populated land for so long—dry prairies with weathered shacks and a few spindly turbines—that Oklahoma City, the 20th largest city in the U.S., came as a shock. After 10 hours on what felt like the surface of Mars, suddenly there were skyscrapers, multilane freeways, and people in a godawful hurry to get between points A and B. It was an American city like any other.

Not really, though. Every place has its quirks and crotchets shaped by land, history, and heroes (who may turn out to be villains, too, depending on your point of view). Every city wants to celebrate and share its culture and make a buck or two off souvenirs. Whatever else our capital cities are, they’re also folk museums herding tourists into the gift shop: Listen to the tales of Boomers and Sooners, and then buy yourself a necklace or cookie cutter.

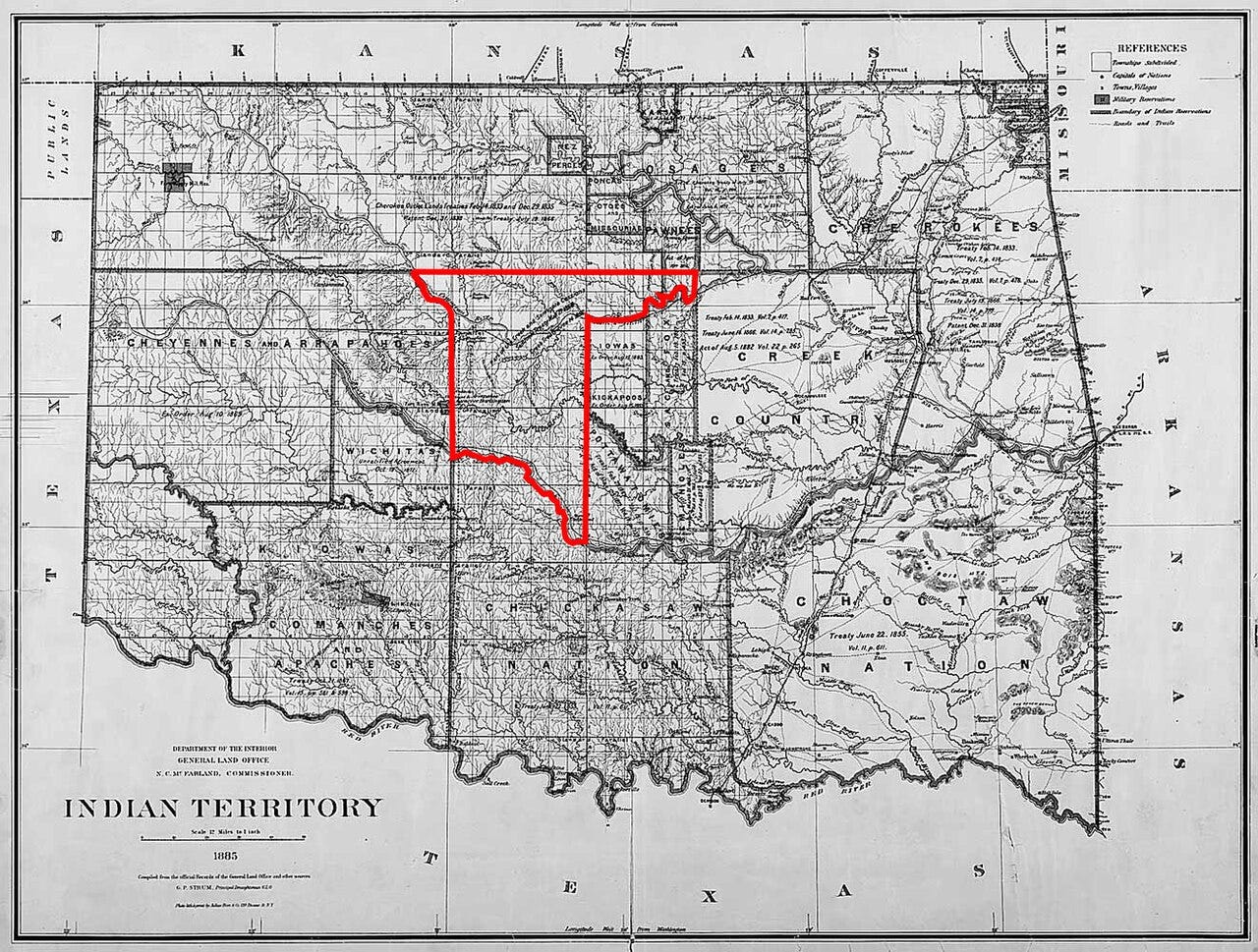

I don’t begrudge them a bit of it. Still, the shape of a state that has no personal associations always looks a bit silly. “The Panhandle” is a metaphor used so rotely now that I’d almost forgotten its origin: the borders of Oklahoma form the shape of a cooking pot with a long handle. It could also be a hand with a finger pointing westward, but that’s not where the collective imagination went, even if it’s where the people went.

As for the history, I had to refresh my memory. Boomers were settlers who rushed to claim land in what is now Oklahoma from 1879–1889. Sooners were those who illegally cut in line during the 1889 land run. Today, the “Sooners” are Okie sports teams. It seems weird to glorify cheaters in such an honest part of the country, but that’s what happens: over time, both historical figures and figures of speech hollow out to mild, jokey versions of themselves. Alternatively, we make romantic icons of whatever we’ve plowed over. (Benign symbols become imbued with sinister meanings, too: searching Oklahoma, I somehow got a story about the OK hand gesture becoming a symbol of hate.)

Where was I? The Land Run of 1889, when thousands of settlers lined up their wagons to vie for plots of land in the “unoccupied Unassigned Lands of Indian Territory.” Wait…if the lands were in Indian Territory, how were they also unoccupied and unassigned? I had to keep backing up to make sense of it.

A congressional amendment to the Indian Appropriation Act opened up almost two million acres of Indian Territory land to American settlers on a “get there first” basis. This mad race—a reality TV producer’s dream—had an official starting date and time: high noon on April 22, 1889. About 50,000 settlers lined up at the border to stake a claim. The Homestead Act of 1862 had proclaimed that any adult U.S. citizen could claim 160 acres of surveyed government land to live on and cultivate, and that number applied to Indian Territory land as well. Interestingly, the Boomers and Sooners included single and widowed women because, despite other limitations on women’s rights, the wording of the Act wasn’t gender specific.

The original Indian Appropriation Act had paved the way for this encroachment by declaring that "no Indian nation or tribe" would be recognized "as an independent nation, tribe, or power with whom the United States may contract by treaty," thus making it easier for the federal government to take back land they’d allocated. Backing up further: the horrific 1830 Indian Removal Act had force-marched Native American people westward. Cherokee, Chicksaw, Choctaw, Creek, and other tribes had been relocated to much of what is now Oklahoma because the land was deemed unworkable. However, as farming and ranching techniques improved, poor and land-hungry settlers began to covet that land, too. Obligingly, the U.S. government took much of it back and put it up for grabs.

Now, there are all these nice Okies selling cooking-pot necklaces alongside Cherokee, Chicksaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Osage reservations where white fools are welcome to gamble their money away. And there was our small group of family and friends from three different states converging for a reunion.

We had rented a house for the weekend in the Paseo arts district, a charming neighborhood that reminded me of Austin 25 years ago before Big Tech moved in and made the Live Music Capital of the World practically unaffordable for musicians. That first night, I got treated to a delicious birthday dinner in a small restaurant that met all our dietary needs (no gluten here, no dairy there, no meat on the left). I started to imagine living in Oklahoma City. Housing is inexpensive, and despite the tornadoes and wildfires, the city has much to offer. What if I picked up and moved there? It was a daydream that reflected my American restlessness, a yearning to load up the wagon and head someplace better. (After one search, Zillow bombarded me with cute OKC houses for sale.)

The next day, we browsed galleries of local art and bought a few pieces of jewelry that were not shaped like cooking pots. (By coincidence, one gallery owner’s daughter was a student at Hollins, A.’s and my alma mater.) Later we took a water-taxi tour of Bricktown, a downtown district bisected by a canal: first Okie Austin and now Okie Venice. Since our tour guide made nonstop bad jokes, I tuned him out and don’t remember much of the spiel. I also was in a bad mood because something completely unrelated to the surroundings had upset me. Those feelings roiled in my stomach, defying my genuine desire to enjoy the moment and the social pressure to Lighten Up Because This Is Supposed to Be Fun. Should a travel blog include such discordant notes? Wherever you go, there you are.

Bricktown used to be a warehouse district storing the freight of four railroad companies. Like old tobacco warehouses in Durham, NC, those long brick buildings have been converted into restaurants and shops that sell 21st-century amusements while romanticizing a gritty history. People on bar and restaurant patios waved to our boat as we glided past, and we waved back.

One of the highlights of the tour was the Oklahoma Land Run Monument.

After stepping off the boat, we ordered takeout on our phones from an Indian restaurant we’d passed on the canal. Then we sipped drinks and talked as we waited for our food. One of us—someone who rarely takes a serious tone—described deliberations with their spouse on whether, for the good of their family, to leave the United States.

I love Oklahoma City. Maybe you should move there. Ha ha. Now I need to go back and enjoy more of it.