If you…think that any thing like a romance is preparing for you, reader, you never were more mistaken. Do you anticipate sentiment, and poetry, and reverie? Do you expect passion, and stimulus, and melodrama? Calm your expectations; reduce them to a lowly standard. Something real, cool and solid lies before you; something unromantic as Monday morning… —Charlotte Brontë, Shirley

The past is never dead. It's not even past. —William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

Despite the literary gravity of those quotes, I have to start at Food Lion. As an introverted geek, I gravitate toward self-checkout. Not only do I get to limit human interaction at the end of a long day, but I get to scan stuff and make the machine beep. (Problematic technology? Yes. Unloved? No.)

But yesterday, because I’d been reading Charlotte Brontë’s Shirley, I walked past the ever-growing bank of isolation stations and chose the lane with human beings behind it. The young cashier called out as I approached, “Yay, we’re bored!” She and her comrade at his grocery-bagging station looked at each other and grinned. I laughed and asked if the whole day had been this quiet; she rolled her eyes, nodded, and then asked how I planned to cook the zucchini noodles. Human interaction is nice, after all. More important, choosing people over machines more often will help the people keep their jobs.

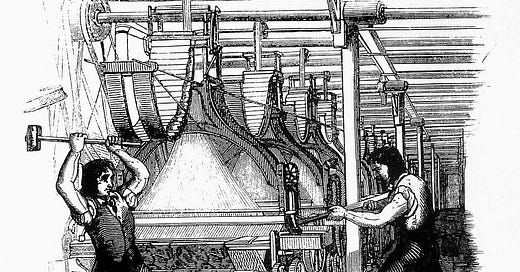

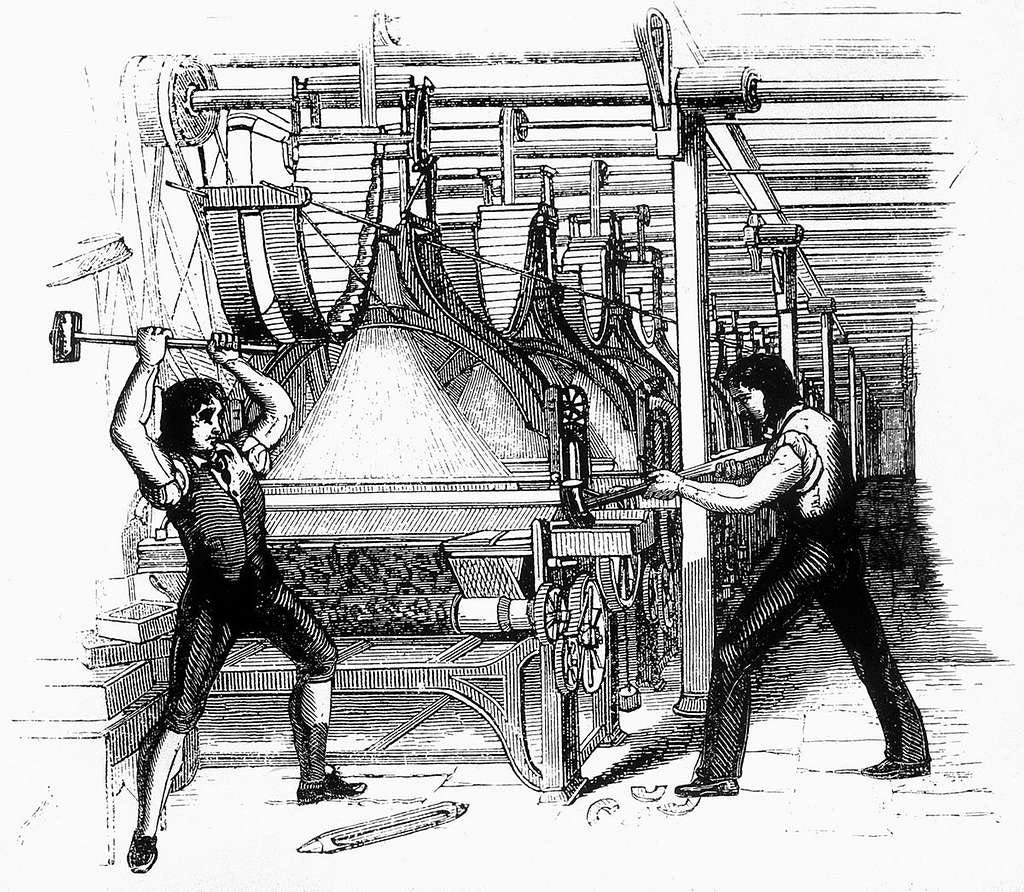

Published in 1849, Shirley was Brontë’s second novel. As the quoted passage above warns the reader, it is a very different kind of story from her wildly successful Jane Eyre. Jane and her romance with the volatile, self-absorbed Rochester were the clear focus of that first novel. (In Jean Rhys’s feminist novel Wide Sargasso Sea, the main character is Rochester’s mad wife.) In contrast, I’m 150 pages into Shirley and haven’t met the title character yet. Apparently, a love triangle will develop eventually despite Brontë’s assurances to the contrary, but I’ve seen no signs of it yet. The novel begins with a gaggle of squabbling curates and then plunges into social unrest. A Yorkshire cloth-mill owner discovers that angry weavers have intercepted wagons full of his new shearing frames. The men have smashed the frames to bits and left the wagon drivers tied up in a ditch. The mill owner, Moore, refuses to bow to pressure: he is all about restoring his family’s lost wealth through industrial progress. The saboteurs, on the other hand, are all about not starving to death.

The term Luddite now connotes anti-technology curmudgeons: my mom, with her stubbornly microwave-less kitchen and old-timey radio, fit this casual usage. (In a nod to her, I’m sipping coffee made with a stovetop percolator and her old manual kitchen timer.) But the early-19th-century English Luddites weren’t driven by some vague fear of or ideological distaste for technology. Artisans turned into saboteurs because the wolf was past the door and gnawing at their children’s stomachs. The replacement of their skilled labor with mindless machines was a matter of life or death, and both factory owners and the government were ignoring their plight. Trade unions were illegal, and in the 1811-1812 time frame of Brontë’s story, only about 3% of English men (and of course, no women) could vote. Powerless against the men who replaced them with machines, the workers could only rage against the machines themselves.

Speaking of children, even the ones with working parents had to labor for their bread. Brontë describes their workday, starting at 6am, with an equanimity that chilled me:

It was eight o’clock; the mill lights were all extinguished; the signal was given for breakfast; the children, released for half an hour from toil, betook themselves to the little tin cans which held their coffee, and to the small baskets which contained their allowance of bread. Let us hope they have enough to eat; it would be a pity were it otherwise.

As for the mill owners, though they were unlikely to starve, they faced ruin, too. War drove the industrial revolution as much as greed: embargoes and counter-embargoes during the Napoleonic Wars had throttled trade and caused food shortages. Trade disputes were one factor that led to the U.S. declaring war on the U.K. in 1812. Cutting labor costs was one way business owners tried to weather these conditions.

Brontë aims for impartiality in exploring the circumstances, motivations, and stances of her characters in a time of economic crisis and social upheaval. She wants us to understand her characters, not judge them. Yet the novelist’s character-delving courtesy has its limits. The gentlefolk and businessmen get to be people with individual minds and hearts; she bestows her sympathy on the peasantry only as a lumped-together mass of sufferers.

Misery generates hate. These sufferers hated the machines which they believed took their bread from them; they hated the buildings which contained those machines; they hated the manufacturers who owned those buildings. In the parish of Briarfield, with which we have at present to do, Hollow’s Mill was the place held most abominable; Gérard Moore, in his double character of semi-foreigner and thorough going progressist, the man most abominated.

England smashed the Luddite movement in 1813 with military might. 14,000 British soldiers—more than were fighting Napoleon at the time—mobilized on English soil to protect the factories against their desperate countrymen.

Brontë started writing Shirley in 1848 in the wake of another period of workers’ unrest: the Chartist Movement. Seeking reform and representation during another economic depression, British workers adopted the "People's Charter" of 1838, written by cabinetmaker and self-educated socialist William Lovett. The charter’s demands, which the English government ignored, included the ballot vote for all men (nope, still not women) and a reconstitution of Parliament as a paid, democratically elected political body with no property requirements for membership. Brontë could not look forward to place the workers’ revolts of her time in the context of the future; but she could look to England’s recent past to shed light on the near present.

Brontë’s limited perspective on workers’ lives was not her fault. As the daughters of an Anglican clergyman, the Brontë sisters had little chance to step outside their proscribed genteel feminine sphere. Their father sent them away to a school so harsh that it became Brontë’s model for the Lowood School in Jane Eyre. Her sisters Maria and Elizabeth both caught tuberculosis there and died. Charlotte later worked as a teacher and governess for a time before returning home to her remaining sisters, Emily and Ann. The three turned to writing and published novels under male pseudonyms. Emily, Ann, and their brother Branwell all would die of tuberculosis while Charlotte was writing Shirley. Charlotte married her father’s curate at age 37 (apparently for love and happily) and then died a year later of complications of pregnancy.

How terse that summary sounds. As with most of us, the most memorable moments of Charlotte’s life probably were the private ones: her and her sisters’ secret snorts of laughter at curates’ pompous squabbling; tender moments with her husband before the fruit of their intimacy cut short her life; the triumph of shepherding and wrestling a draft to its end by the late-night light of a lamp. It’s a miracle that any of us try to do anything to make the world better. It was not Charlotte’s job to, as Virginia Woolf wrote of her Mrs. Ramsay, “elucidate the social problem.” Yet from her small sphere of kitchens and parlors, she saw the misery behind the Luddite and Chartist movements and set them in meaningful context as best she could.

We can’t see our own time in light of the future, either. As C.S. Lewis observed, it would be helpful if we could get at the books that haven’t been written yet; since we can’t, the only way to escape the blind spots of our own time is to visit the past, whose errors are obvious and therefore no threat. There is no chance, for example, that I’m going to join Brontë in taking phrenology or class boundaries seriously. The bumps on our heads and the accidents of our birth are not our fates.

Like Charlotte, we don’t even have to look back that far. This Labor Day I offer a 1964 Twilight Zone episode1 that speaks to us not so much about smart machines (check out those silly beeping boxes!) as about the value of human connection and the dangers of pride and greed. Sooner or later, soulless automation is a self-own.

Mr. Whipple: middle-aged Americans will recognize the greedy king of efficiency as the “don’t squeeze the Charmin” guy.

Luddites had their reasons and their catastrophic predicament. I don't like that the word is used as "anti-technology" generally, as we can all use our smarts to use tech for good and reject the bad, and studies seem to show most people doing that with social media, for example. I opposed our governor's giveaway of laptops to 7th-8th graders based on research about learning, and for the fact that there was no consideration for training teachers to use the tech and no care about the unbudgeted expenses that would take away, for example, music and art in many places. Not to mention the fact that having access to the whole Louvre online means nothing if kids have no idea what art is about, what it looks and feels like and means... This is a great & well-written article, Jody, for many reasons, especially for Labor Day, full of really interesting facts. Tragic facts. Including how the Bronte kids died. And we have entitled people who don't feel like getting vaccinations, people who are mistakenly proud of being "Luddites" against medical progress.

I'm a proud Luddite. When I can avoid technology, I do. Sadly (yet in many cases, thankfully), it's everywhere anymore. I never ever use self-checkout and stopped going to Wal-Mart a couple years ago when they implemented it everywhere. I won't be going back either. As a writer, I've come to reluctantly embrace a lot of technology for that but that AI-generated crap will never be a part of it. I taught this word in my Linguistics class years back -- I'd go over many eponyms, and this word was my favorite one.