The Past Is Always Present

Thoughts on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. Or: come back, Frances Perkins.

Today I meant to write about Alice Stone Blackwell and the friendship with an Armenian refugee that led to her publishing translations of Armenian poems. But then I started reading Blackwell’s biography of her mother, Lucy Stone, and became entranced with the story of that Massachusetts suffragette, abolitionist, teacher, and all-around badass. I’m about halfway through, so I’ll save mother and daughter for next time. Today I’m thinking about another reformer and the tragedy that changed her into the person the country most needed.

For the record, my tolerance for pathos is zip these days. On a work project recently, I got teary eyed over a “Remember the Lusitania” WWI enlistment poster. I mean, really. (On the bright side, who better to write about emotional appeals than somebody who’s ridiculously susceptible to them?) So the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire is almost unbearable to even think about. That tragedy—no, that mass murder—was pathos to end all pathos. It changed everything in the United States. In particular, it aimed one woman like a flaming arrow: a young Massachusetts labor investigator and activist named Frances Perkins.

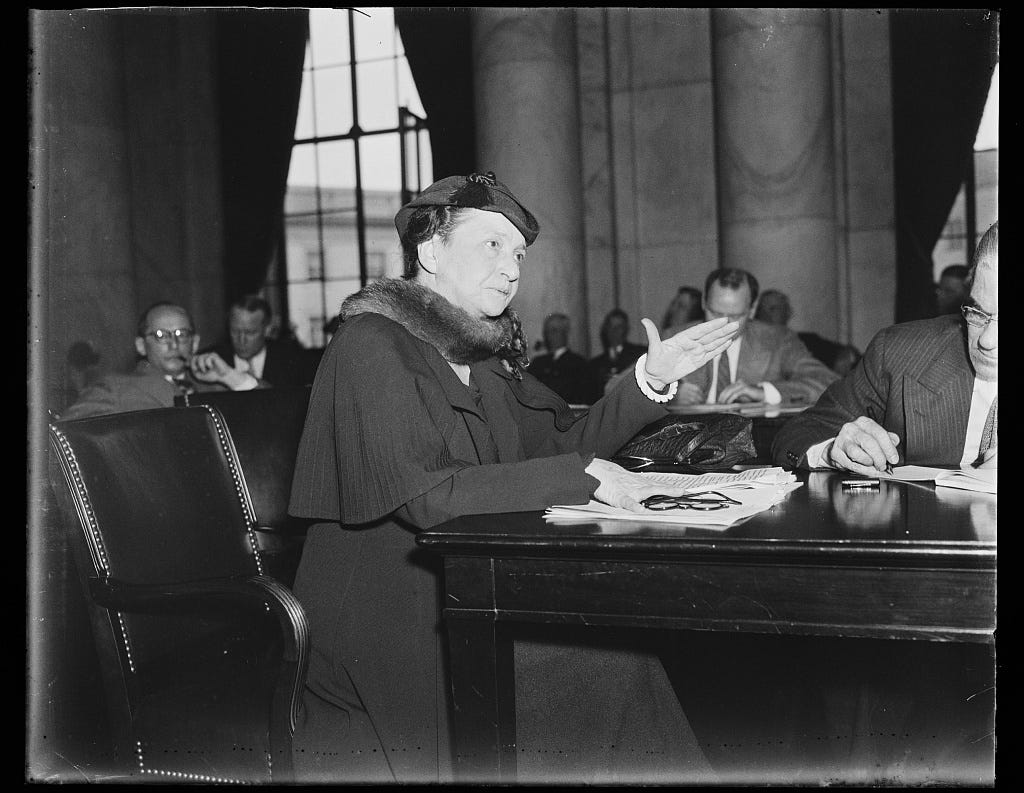

Later, Perkins would become known as “the woman behind the New Deal.” As Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor—the first woman to serve in a U.S. cabinet position—she would be the driving force behind the Social Security Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act. But in 1911, she was a 31-year-old woman with no real political power except her persistence. She couldn’t even vote. On March 25, 1911, she was at a ladies’ tea in New York, just blocks from the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

The Triangle factory was a sweatshop unconstrained by labor laws or common decency. (In the absence of the former, the titans of industry demonstrably had little of the latter.) Mostly immigrant girls and women—Italian, Russian, Hungarian, German; many speaking only their native national language or Yiddish—worked for 12 hours a day, 7 days a week, for $15/week. The owners, Blanck and Harris, had ignored the demands of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union for better pay and safer working conditions the year before. Instead of listening, they had bribed officials and hired thugs to beat and arrest the girls and women on picket lines.

The “shirtwaist kings” refused to install basic fire safety measures despite repeated warnings of the dangers. Evidence suggests they may have previously torched their own businesses to collect big payouts from fire-insurance policies. Toward that end, sprinkler systems just wouldn’t do. What also wouldn’t do were unlocked doors: they feared theft and didn’t want workers slipping out for unauthorized breaks.

The workers were on the eighth floor of the building. On Saturday, March 25, it was quitting time and payday; they were already putting on their wraps and hats. Then someone tossed a still-lit cigarette into a wastebasket. The fire spread to all the flammable cloth, and within minutes, the whole floor was on fire. The one unlocked staircase was quickly engulfed in flames.

A factory worker named Mary Domsky-Adams later said:

My own machine was located near the locked front doors, and I often looked with fear at the darkness that loomed through the half-glassed door, which made me feel as if some secret force were peering out from there. And it was before this door that the greatest number of victims were caught; they had surged to the door, hoping to escape, but couldn’t break through, because the door always was securely locked.

The only fire escape collapsed under the weight of panicked people. The elevators also broke down. The firefighters’ ladders reached only to the sixth floor. Trapped with flames at their backs, girls locked arms and jumped from the windows together with their dresses on fire. Nets held out to catch them tore like paper or were wrenched from the men’s hands.

I read the New York Times article on the fire from March 26, 1911, and felt stunned by the gruesome details. Journalism was not gentler or more restrained back then; the article was lurid in ways that we now associate with “rags.” It also framed all the female victims as hysterical and all the heroes as male, though the truth was far more complex and poignant.

Many people were heroic that day. Three men formed a bridge of their bodies to a window of the next building and then fell to their deaths after others climbed over them to safety. We now know that another hero of the Triangle fire was a 21-year-old Lithuanian forewoman named Fannie Lansner. Lansner went from room to smoke-filled room and calmly led out groups of women to a working elevator, ignoring their pleas for her to come with them. In the end, she lost her chance and had to jump to her death. Her descendants still honor her.

Before jumping, one young woman sent her hat sailing from the window and carefully emptied her meager week’s pay from her handbag, a few bills and coins, as a gift to the crowd below. (Or was it a bitterly ironic gesture: look how little I’m dying for?) Another stood in a window frame and spoke with impassioned sweeps of her arms before stepping into the air. No one could hear what she said. A young man, people burning behind him, gently helped three young women to an easier end before jumping himself. The last girl put her arms around him and kissed him before he lowered and dropped her.

When Frances Perkins got word of the fire, she hitched up her skirt and ran to the scene. Along with thousands of others, all she could do was watch in horror. At first, they thought workers were tossing bundles of valuable cloth out the window to save it. Then they realized the falling bundles were people.

There was a stricken conscience of public guilt and we all felt that we had been wrong, that something was wrong with that building which we had accepted or the tragedy never would have happened. Moved by this sense of stricken guilt, we banded ourselves together to find a way by law to prevent this kind of disaster.

Eyewitness reporter William Shepherd drew the connection to the workers’ brutally squelched strike the year before:

I looked upon the heap of dead bodies and I remembered these girls were the shirtwaist makers. I remembered their great strike of last year in which these same girls had demanded more sanitary conditions and more safety precautions in the shops. These dead bodies were the answer.1

The Triangle fire shocked the American conscience in a way that changed everything—for a while. Now after a few generations of no American children slaving in coal mines and no workers leaping out of windows, some people are trying to tear up the legal safety nets. Others want to ban any American history lessons that make students uncomfortable. In 1911, it was collective discomfort of the most acute kind that caused Americans to link arms and push through protective legislation.

At the time of the fire, Frances Perkins wasn’t only having tea. She was in New York lobbying to end child labor. How appalled she would be to see her work being undone state by state in the name of freedom and industry. But this is what happens when people forget. The past is always present, whether we see it or not.

Oh, Blanck and Harris? They were indicted but went free. They collected insurance money from the fire. Two years later, Blanck was caught locking workers into his Fifth Avenue factory. He paid a $20 fine.

Stein, Leon. The Triangle Fire. United States, Cornell University Press, 2010.

I wondered the same since she would not talk about it at all. I feel for all the children slaving in mines, and now reading that the work age may be lowered to 14 in some states.

Thank you, Jody, for writing this.

It also bothers me very much that state legislatures are writing and passing "laws" that allow employment of children. I wonder if the federal government could override these state "laws".