Things Invisible to See missed a week…my brain was just too fried to rub two more thoughts together. In educational publishing land, sixth grade is up, and I’ve been developing content for a couple of different clients.

Specifically, I’ve been writing short passages that will become the basis for test questions. Each mini-essay focuses on a pre-selected topic and tucks into its folds the language skills taught in a unit of the textbook. It’s like writing a sestina, except with “intensive and reflexive pronouns,” “domain-specific vocabulary,” and “similes and metaphors” instead of “six stanzas of six unrhyming lines, each stanza ending with the same six words in a set pattern, followed by an envoi of three lines.” OK (cough), it’s nothing like writing a sestina, except that both try to sound natural while being carefully contrived.

To the point of this post, two of those topics gripped my attention and imagination so strongly that I’m still thinking about them. (Do kids know that the writers of their lessons and tests are still learning stuff? That if we’re lucky, we never stop learning?)

If Only I’d Been Modeling Irony

Last Thursday was summer’s last hurrah here in Virginia—sunny and 70 degrees—and I was cooped up inside all day writing (I’m not making this up!) a passage for kids on why we all need to get outside more. But seriously, the research for that piece shook me up. Watch marine biologist Tierney Thys explain how indoor life is harming our physical and mental health.

After hearing that too little sunlight on our eyeballs lengthens them and causes myopia, I can’t see the typical American school schedule as anything but child abuse. What kind of little Frankenstein monsters are we making from Common Core parts? (Sorry, I’m still in Halloween mode.)

The flip side of the story is that time in nature can heal us in unexpected ways. Most of us know this intuitively—who doesn’t feel refreshed by a stroll along a stream in the sunshine?—but few of us make time to “walk the walk.” The Japanese practice of shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing,” builds a ritual around the simple act of walking mindfully in a natural environment. “Forest bathing” also serves the forests themselves by inspiring people to protect them. We care most about the places we’ve seen, touched, and smelled—not so much, unfortunately, about those whose health connects with ours through a vast, invisible web.

When a Girl Fell from the Sky

The other topic that I can’t stop thinking about is the extraordinary story of Juliane Diller née Koepcke.

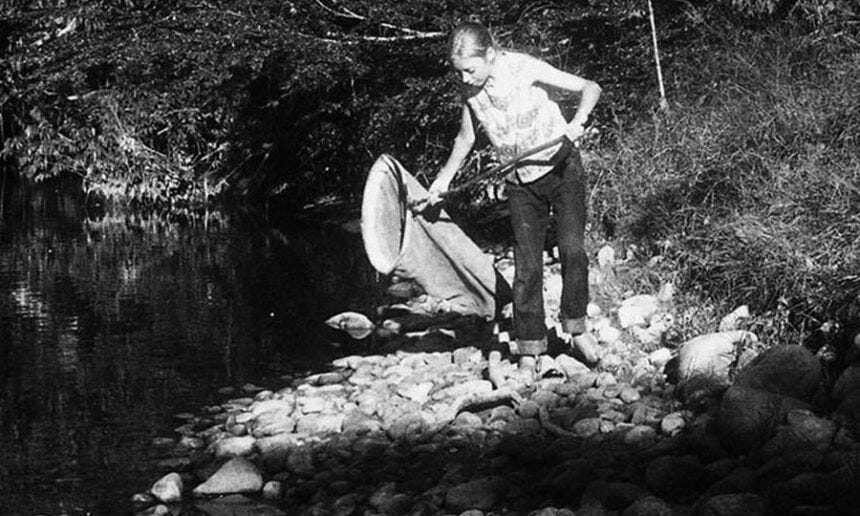

Juliane was the daughter of German biologists who lived and worked in Peru. Her parents founded Panguana, the oldest research station in the Peruvian rainforest. Born in Lima, Juliane was homeschooled from Panguana for two years until school authorities expressed alarm that she was growing up as a jungle baby. They insisted she return to Lima to take her exams and finish high school. She passed the tests and graduated at the end of 1971. On Christmas Eve, she and her mother were heading back to Panguana to spend the holiday together as a family.

Events would show that thanks to her unusual upbringing, Juliane knew the answers to questions never asked on tests. For example, if you have fallen from an airplane into the Amazon rainforest and find yourself still alive, it’s safer to travel in the water than on land. You should keep your one remaining sandal on your foot to feel for poisonous snakes, especially if you have lost your eyeglasses. Gasoline can flush maggots from a festering wound. Above all—because you are utterly alone in your one sandal and torn minidress and have to save yourself—keep going.

You can read the story of the plane crash and Juliane’s survival here.

You can also watch Werner Herzog’s 1998 documentary Wings of Hope. For Herzog, the story of that crash and a fellow German’s ordeal was personal: location scouting in Peru in 1971, he was supposed to have been on that doomed flight but changed plans at the last minute.

While she stumbled and swam through the sweltering rainforest for 10 days with stingless bees covering her face, Juliane told herself that if she survived, she would devote her life to “a meaningful cause that served nature and humanity.”

Her cause became Panguana. She went to Germany, got her doctorate in biology, and then went back to Peru to study bats. She married an entomologist who specializes in parasitic wasps. In 2000 after the death of her father, she became the director of the research station her parents had founded.

Do bats and wasps seem anticlimactic? They did to me until I remembered that entire ecosystems depend on bat colonies. Parasitic wasps are undoubtedly important in little-known ways, too. How many Panguanas are there in remote jungles where researchers do essential, little-regarded work to serve nature and humanity?

I’m also thinking about the deforestation that Juliane’s parents worked hard to protect Panguana from. I just came across yet another alarming article, “The Amazon Is Fast Approaching a Point of No Return.” Scientists have been sounding this alarm for decades: the fate of the rainforests is the fate of our children. Does something need to fall out of the sky onto our heads for the grownups to listen before it’s too late?

Something is very wrong when children tick the right box for a reflexive pronoun but get too little sunlight on their eyeballs; when kids have heads full of grammar but don’t know that food grows in the ground. And I’m afraid that “something wrong” is having disastrous repercussions for our home planet.

When Juliane fell toward them from the sky, the treetops looked like “heads of broccoli.” The earth is not just what we walk on, what we eat and burn for fuel; it’s the language of our experience and ourselves.

Our intellectual heritage is important to pass on—I wouldn’t even think to question that. But I want to ask with poet Richard Wilbur whether our treasured metaphors will still have meaning when their natural sources are gone:

Ask us, ask us whether with the worldless rose

Our hearts shall fail us; come demanding

Whether there shall be lofty or long standing

When the bronze annals of the oak-tree close.

—Richard Wilbur, “Advice to a Prophet”

Another great and interesting read. Love your prose, and always learn something new!